Balochistan: Land of Hospitality, Resources, and Beauty

Balochistan: Land of Rich Resources and Culture

Balochistan, the largest province of Pakistan, is known for its vast resources and strategic location. The mining sector plays a crucial role in the economy, with abundant minerals such as coal, copper, gold, and natural gas. Despite covering 43.6% of Pakistan’s land, its population density remains low, as per the 2023 census. The development of its infrastructure faces challenges, yet ongoing initiatives and investments aim to unlock its true potential.

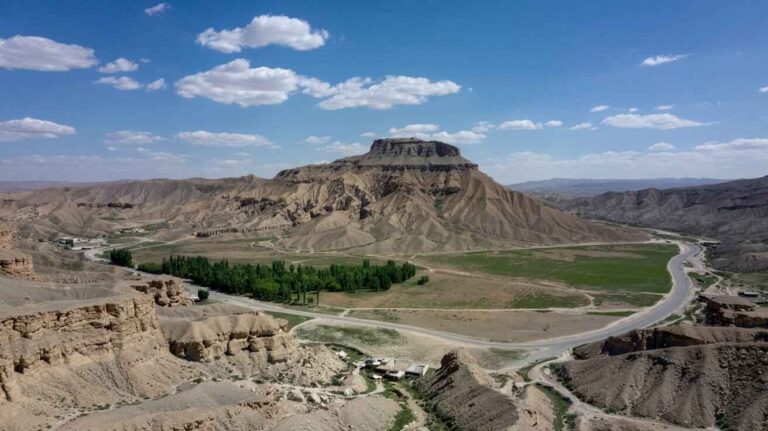

With a 760 km coastline along the Arabian Sea, including Gwadar and Pasni, Balochistan holds immense value for trade and regional prosperity. Its diverse ethnic groups, including Baloch, Pashtuns, and Brahuis, enrich its heritage and traditions. The province’s rugged landscape, from the desert to mountain ranges, and the vast Makran region covering 36,000 sq. km, add to its unique identity. Ensuring growth while preserving cultural diversity remains key to shaping its future.

760km Coastal-line of Balochistan

The 760 km coastline of Balochistan along the Arabian Sea holds great importance for trade and economic growth. Key port cities like Gwadar and Pasni make the region a gateway for regional and global commerce. The coastline is not just a hub for the economy but also a source of livelihood for local fishing communities. With increasing investments and development projects, this coastal belt has the potential to bring prosperity to the province. However, infrastructure challenges remain a hurdle in unlocking its full benefits.

Beyond its economic value, the coastline reflects the region’s rich heritage and traditions, shaped by diverse ethnic groups like the Baloch, Pashtuns, and Brahuis. The stunning landscape, featuring the vast Makran region and rugged mountain ranges, adds to its uniqueness. Despite the low population density recorded in the 2023 census, the area’s potential for tourism and industry remains high. Addressing challenges and ensuring sustainable development will be key to maximizing this strategic asset.

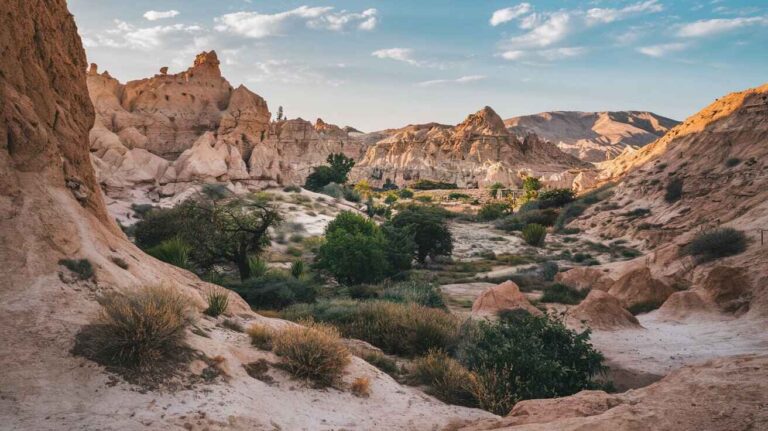

The Vast and Rugged Makran Desert ( 36,000 sq km desert )

The Makran Desert in Balochistan, Pakistan, spans an enormous 36,000 sq. km, covering a significant land area with its rough terrain and scattered plateaus. The region’s basins and towering mountain ranges add to its ruggedness, making travel and settlement challenging. With an extremely dry climate, only 5% of the land is arable, limiting agriculture but supporting livestock farming. Despite these hardships, the desert holds valuable resources, including natural gas, which can contribute to the economy if properly utilized.Cities like Quetta, Turbat, and Gwadar are crucial in transforming this emerging region into a business hub. However, development faces numerous challenges, including inadequate infrastructure and limited investments. Various initiatives aim to improve conditions and bring prosperity to the desert communities. If strategic efforts continue, this harsh yet resource-rich landscape could become an essential part of Balochistan’s future growth.

Early history

The southeasternmost region of the Iranian Plateau, Balochistan has been home to some of the earliest known farming settlements, predating the Indus Valley Civilisation. The site of Mehrgarh, dating back to 7000 BCE, marks the westernmost extent of this ancient civilisation. Over time, the region saw the rise and fall of various rulers, including the Paratarajas, an Indo-Scythian dynasty, and the Kushans, who exerted political sway over the area. In the seventh century, Islam spread across the region, influencing its culture and governance.

The Sewa Dynasty, linked to Hindu rule, once governed parts of Kalat, Sibi Division, and Quetta Division, with Rani Sewi as a notable queen. Legends connect the region to King Kay Khosrow of Iran and the Kayanian dynasty. The Baloch people, who became the largest ethnic group by the 14th century CE, are believed to have Median descent. The Brahui, an indigenous Dravidian group, add to the region’s diverse heritage. Ashkash and Makran hold remnants of ancient settlements, tracing back to the Stone Age and Bronze Age. Even Alexander the Great passed through these lands, leaving behind a legacy of historical significance.

The Spread of Islam in Balochistan

In 654, during the Rashidun Caliphate, Abdulrehman ibn Samrah, the governor of Sistan, led an Islamic army to suppress a revolt in Zaranj, extending Muslim influence into southern Afghanistan and north-western Balochistan. His forces advanced through Kabul, Ghazni, and the Hindu Kush, eventually reaching the Quetta District, Dawar, Qandabil, and the Bolan region, establishing early settlements. By 663, under the Umayyad Caliph Muawiyah I, Haris ibn Marah led another army into north-eastern Balochistan, facing resistance in QaiQan and Kalat. Despite challenges, Muslim rule spread across Makran, shaping the region’s future.

Pre-modern era

In the 15th century, Mir Chakar Khan Rind, a powerful Sirdar, unified the Baloch tribes across Afghan Balochistan, Iranian Balochistan, and Pakistani Balochistan. He initially pledged allegiance to the Timurid ruler Humayun, later shifting alliances as the Mughal Empire and Nader Shah vied for power. The Khanate of Kalat emerged as a key force in eastern Balochistan, navigating conflicts with the Kalhora rulers of Sindh over the Sibi-Kachi region. During the rise of the Afghan Empire, Ahmad Shah Durrani extended Afghan rule into Baloch lands, with Baloch warriors even participating in the Third Battle of Panipat, though they maintained significant local control.

Colonial era

The Bolan Pass played a crucial role in historical trade and military movements, connecting northern Baluchistan with the rest of colonial India. During the expansion of British India, the region, once part of the Durrani Empire until 1823, saw increasing British influence. By 1876, Sir Robert Sandeman negotiated the Treaty of Kalat, placing Kalat, Makran, Kharan, and Las Bela under British protection. The Second Afghan War led to the Treaty of Gandamak in May 1879, giving the British control over Quetta, Pishin, Harnai, Sibi, and Thal Chotiali. By April 1883, the British fully secured the Bolan Pass, and by 1887, parts of Balochistan were formally declared British territory. The Durand Line, drawn in 1893 by Sir Mortimer Durand and Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, set the border between British-controlled areas and Afghanistan.

Throughout the early 20th century, Balochistan’s politics became increasingly active in the Indian independence movement. Groups like the Muslim League and Anjuman-i-Watan Baluchistan debated whether Balochistan should join a united India or support partition, leading to opposition from various factions. The region also suffered devastating earthquakes, including the Quetta earthquake of 1935 and the Balochistan earthquake of 1945, with the epicentre near Makran, causing widespread destruction.

Geography

Balochistan is the largest province by area, covering 347,190 square kilometers (134,050 sq mi), making up 44% of Pakistan’s total landmass. Located in southwest Pakistan, it shares borders with Afghanistan, Iran, Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, while its southern coastline meets the Arabian Sea. The province is part of the Iranian plateau, connecting South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East. The Strait of Hormuz, a vital trade route, gives Balochistan the shortest seaport route to Central Asia, attracting global interests. The Bolan Pass, historically used for Afghanistan invasions and controlled by British rulers, remains a key link between Central Asia and South Asia.

The landscape is rugged, with the Sulaiman Mountains in the northeast and desolate regions covering much of the province. Quetta, the capital city, is an important trade hub due to its proximity to Kandahar. Astola Island, Pakistan’s largest offshore island, lies off the Makran coast. The province is rich in natural gas and serves as Pakistan’s second major supplier, but concerns about exhaustible resources persist. However, renewable resources like solar and wind energy, along with sustainable water sources, could support local inhabitants, who have lived here for thousands of years. The development of human resource potential remains crucial for the province’s future.

Extreme Weather Across Balochistan

Balochistan’s climate is as diverse as its landscape, shifting dramatically from very cold winters in the upper highlands to extremely hot summers in the plains and arid zones. Living in this region, I’ve personally experienced how these variations shape daily life, from cozy winter nights in Ziarat to scorching afternoons in Sibi, where the sun feels unrelenting.

In the upper highlands, winters can be brutally cold, with temperatures plunging as low as −20 °C (−4 °F). The snow-covered peaks create a breathtaking view, but survival requires heavy woolen clothing and heated shelters. Summers, on the other hand, are hot, yet the temperature fluctuation between day and night is noticeable. This contrast is felt strongly in places like Quetta, Kalat, Muslim Baagh, and Khanozai, where people adjust their routines to cope with the extremes.

Moving to the lower highlands, the northern districts endure extremely cold winters, making heating essentials a priority for residents. However, as one travels closer to the Makran coast, winters become relatively milder, creating a more comfortable environment. The influence of the Arabian Sea moderates temperatures, making coastal living a preferred choice for those who want to escape the harsh cold of the highlands.

The plains of Balochistan, however, tell a different story. Winters here remain mild, with temperatures rarely dipping below freezing. But summers are extremely hot, often reaching a blistering 50 °C (122 °F) or even higher. The heatwave in Sibi on 26 May 2010, where the temperature soared to a record 53 °C (127 °F), stands as a reminder of the intense summer conditions.

The arid zones, including Chagai and Kharan, experience harsh hot and dry summers. Rain is scarce, making water a precious resource. Traveling through these regions, one can feel the land’s struggle against the sun, with little vegetation surviving under the relentless heat.Similarly, the deserts of Turbat and Dalbandin are infamous for their very hot and arid conditions. The dry air combined with frequent windstorms creates an inhospitable environment, making survival dependent on deep wells and traditional cooling methods. The way locals adapt to this unforgiving climate, using architectural techniques like thick mud walls and underground storage, is a testament to their resilience.

The Political Structure of Balochistan

The political landscape of Balochistan is shaped by its parliamentary system, where the provincial assembly holds 65 seats, including 11 reserved for women and 3 reserved for non-Muslims. The Governor, who serves a mostly ceremonial role, is appointed by the President of Pakistan on the advice of the executive. The Chief Minister is the head of the provincial government and is elected by the majority in the assembly. Various political parties, including Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, Pakistan Muslim League (N), Pakistan Peoples Party, Balochistan National Party (Mengal), and National Party, influence the political dynamics of the province.

The Balochistan High Court in Quetta oversees judicial functions as part of the judicial branch, with the Chief Justice ensuring legal matters are addressed. The assembly operates as a unicameral body, where national parties and local groups compete for influence. The political scene remains complex, with governance challenges and shifting alliances playing a major role in shaping the political dynamics of Balochistan.

Divisions of Balochistan

For administrative purposes, Balochistan is divided into eight divisions and 36 districts. Initially, the seven divisions—Kalat, Makran, Nasirabad, Quetta, Sibi, Zhob, and Rakhshan—formed the core of the provincial administrative structure. However, in June 2021, a new Loralai Division was created by bifurcating Zhob Division, increasing the total number of divisions.The system has seen changes over the years. Divisional level governance was abolished in 2000 but later restored after the 2008 election. Each division is headed by an appointed commissioner, who oversees the districts within their subdivision. These provinces and districts form the backbone of Balochistan’s governance, ensuring efficient administration across its vast and diverse landscape.

Etymology The Origin of the Name Balochistan

The etymology of Balochistan is deeply connected to its people, particularly the Baloch. Scholars have traced the name back to the 10th century, with some linking it to pre-Islamic sources. The historian Johan Hansman suggested a connection between Baluḫḫu—a term found in the records of the Neo-Assyrian Empire—and the ancient region of Meluḫḫa, believed to be part of the Indus Valley civilisation. Others, like H. W. Bailey, associate it with underground channels used for irrigation, known as uadravati.

Arab geographers like Al-Muqaddasī referred to parts of Makran as Bannajbur and mentioned the term Balūṣī, which evolved into Baluchi. Linguists such as Asko Parpola and Romila Thapar link it to Indo-Aryan words like mleccha or milakkha, which were used to describe outsiders. The proto-Dravidian term milu-akam, meaning high country, resembles Tamilakam and melu-akam, referring to Dravidian-speaking regions. Some even speculate connections to Alexander the Great’s expedition, where ancient texts referred to the region as Gedrosia and its people as Gedrosoi, reflecting Balochistan’s role as the western extremity of historical empires.

Balochistan After Independence

Following the partition of India in 1947, the status of Balochistan remained uncertain. Under British rule, it consisted of British-controlled areas like Nasirabad, Nushki, and Bolan Agency, and four princely states—Kalat, Makran, Las Bela, and Kharan. The Chief Commissioner governed the former, while the latter maintained relative autonomy. The Shahi Jirga and Quetta Municipality held a grand council vote, deciding unanimously in favor of Pakistan, a move some questioned in terms of legitimacy. Qazi Muhammad Isa and the Balochistan Muslim League worked closely with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who claimed the accession reflected the true will of the Baloch people.

However, opposition emerged. The Khan of Kalat, Ahmad Yar Khan, initially resisted signing the Instrument of Accession, leading to negotiations and, eventually, annexation. His brother, Prince Abdul Karim, led a rebellion in Dosht-e Jhalawan, engaging in guerilla-style attacks against the Pakistani military in 1950. Subsequent Baloch nationalist insurgencies erupted in 1948, 1958–59, 1962–63, and 1973–77, with autonomy-seeking Baloch groups continuing resistance into 2003. Some figures, like Salman Rafi Sheikh, argue that the province’s integration involved political manipulation and disenfranchisement. Recent conflicts involve allegations of terrorism, as seen in Sarfraz Bugti’spress conference, where he accused India’s RAW of fueling unrest. With the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and Gwadar’s strategic role, Balochistan remains at the center of geopolitical tensions, shaped by its Omani heritage and historical struggles.

High Court of Balochistan

The Balochistan High Court has a unique history among Pakistan’s provinces. Initially, the region was under the High Court of West Pakistan, established in October 1955. Before that, a Judicial Commissioner handled cases. However, this system was dissolved in July 1970, leading to a joint High Court for Sindh and Balochistan. It wasn’t until November 1976 that the two provinces got separate high courts, and by December 1976, the High Court of Balochistan became fully operational, with Justice Khuda Bakhsh Marri serving as the first Chief Justice, alongside Justice M. A. Rasheed and Justice Zakaullah Lodhi.

During its first decade, the court had only five judges, but today, it comprises fourteen judges. Originally housed in the Sessions Court building on Zarghoon Road, a newerHigh Court complex was planned. The project started in 1987, and after seven years, the building on Hali Road was completed in 1993. The court spans 5.03 acres, with a covered area of 115,371 sq. ft. within a total 219,107 sq. ft. space. The structure includes a ground floor, first floor, mezzanine, podium arcade, ancillary blocks, and a frill area, reflecting a modern judicial infrastructure.

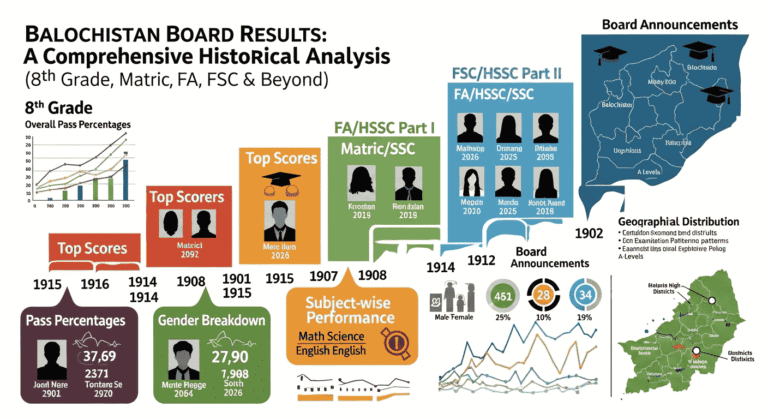

Division , Districts and Population of Balochsitan

Here is a properly formatted table for the given data:

| Division | Districts | Population | Area (km²) | Area (sq mi) | Density (per km²) | Urbanization Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kalat | Awaran, Hub, Kalat, Khuzdar, Lasbela, Mastung, Surab | 2,721,018 | 91,767 | 35,431 | 29.65 | 38.72 |

| Loralai | Loralai, Barkhan, Musakhail, Duki | 870,000 | 17,260 | 6,660 | 50.41 | 39.89 |

| Zhob | Zhob, Killa Saifullah, Sherani | 927,579 | 27,128 | 10,474 | 34.19 | 32.33 |

| Makran | Gwadar, Kech, Panjgur | 1,875,872 | 52,067 | 20,103 | 36.03 | 47.69 |

| Naseerabad | Kachhi, Jaffarabad, Jhal Magsi, Nasirabad, Sohbatpur, Usta Muhammad | 2,044,021 | 15,129 | 5,841 | 135.11 | 32.59 |

| Quetta | Killa Abdullah, Karezat, Pishin, Quetta, Chaman | 4,259,163 | 14,559 | 5,621 | 292.55 | 51.68 |

| Rakhshan | Chagai, Washuk, Nushki, Kharan | 1,040,001 | 98,596 | 38,068 | 10.55 | 36.84 |

| Sibi | Sibi, Kohlu, Dera Bugti, Ziarat, Harnai, Lehri | 1,156,748 | 30,684 | 11,847 | 37.70 | 34.70 |

Customs and Traditions of the Baloch People

The Baloch community has a deep-rooted tribal structure that shapes its traditions and way of life. Loyalty to Tumandars or Sardar remains central to the social order, though some non-tribal Baloch communities also exist. Their customs reflect a strong sense of identity, emphasizing hospitality, justice, and collective support. From ancient times, the lifestyle of Baloch nomads has revolved around self-sufficiency and resilience, adapting to harsh landscapes while maintaining their traditions.

One of the most cherished values among the Baloch people is Lajj o Mayaar (Mayar jali), which emphasizes extreme hospitality. A guest, regardless of background, is treated with honor, and it is customary to offer food, shelter, and protection. Similarly, Mehr plays a crucial role in their emotional connections, where love and enmity are held at the highest levels. A Baloch considers a friend like family and an enemy as someone to be avoided or opposed with strong conviction.

The tradition of Hak Peheli is a powerful gesture of reconciliation, practiced on Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Fitr. It involves hugging three times after the prayer, symbolizing forgiveness and the willingness to let go of past grievances. This act strengthens community bonds and reminds individuals of the importance of peace. Another integral practice is Diwan, a gathering where Sardars and tribal elders come together to discuss issues concerning the people. These meetings ensure fair decision-making and uphold tribal unity.

A lesser-known but fascinating custom is Mesthaagi, which involves rewarding someone who delivers good news—such as the birth of a son or the return of a lost relative. This tradition reflects the Baloch people’s appreciation for positivity and the value of sharing joy within the community. Likewise, Bijjaar is a form of collective financial support provided during times of marriage or death, ensuring that no one in the tribe faces hardship alone. At times, the Sardar himself initiates Bijjaar, encouraging tribal members to contribute for those in need.

Beyond these structured customs, Baloch people also hold strong beliefs in supernatural forces. Many believe in the power of the wind and sea, seeing them as forces that can shape destinies. The concept of nazzar (evil eye) is taken seriously, with protective measures often in place to ward off bad luck. Similarly, stories of jinn are deeply embedded in folklore, with many believing that crossing into their domain can bring misfortune.

These customs and beliefs make up the rich cultural fabric of Balochistan, preserving its heritage through generations. Whether through communal gatherings, acts of generosity, or spiritual convictions, the Baloch people continue to uphold traditions that define their identity.

Customs and Beliefs

In Baloch people‘s traditions, taking an oath is an important principle to prove innocence or settle disputes. One such ritual, known as Var ritual, was common in many regions of Balochistan nearly fifty years ago. This practice involved different forms of oath-taking, such as the oath of the Quran, the Nal oath, and even passing through fire in extreme cases. In the southern regions, a ritual called Api Sogand was performed to prove honesty, where a person would swear on fire and water. Depending on the severity of the case, people took either the cold Var, which involved swearing on sacred elements, or the hot Var, where individuals placed hands on a hot rod or even hands on the hot stone to demonstrate truthfulness.

One of the most famous Balochi folk stories tells of Shahdad and Mahnaz, where Mahnaz’s consent played a crucial role in proving love and loyalty. Such tales reflect the deep cultural roots of these pre-Islamic traditions, which some Baloch tribes still remember. The Taftan region and nearby areas also had unique rituals, influenced by bilingual influences like Parsiwani and the Balochi language. These traditions have slowly faded, but they remain a fascinating part of Balochistan’s heritage.

Traditional games

In Baloch culture, traditional games have been passed down as a legacy from the past, keeping the spirit of competition and unity alive. In Iran, especially in Kerman, games like Chal bazi are popular, where two teams of equal numbers compete by splashing water in a swimming challenge. Another well-known game, Kala chal chal, involves players forming a circle and trying to run while grabbing a hat before others catch them. Similarly, Kapag is enjoyed by children and teenagers, where they form circles and engage in a playful fight, combining holding legs and pushing techniques.

Among rural communities, games like Lagosh are commonly played near palm groves, where one participant takes the role of a wolf and chases others. Pag and dastar, both referring to a turban, are used in games where a knitted form of the turban is thrown, and whoever hits it first becomes the next player. Camel riding is one of the most famous indigenous sports, especially in Khash, Iranshahr, and parts of Nimruz, Afghanistan, where riders compete on special occasions. Riding horse and Horse race remain essential for training young men, with archery serving as a practical training method. The Balochi horse, a native breed, is often used in these competitions, preserving a deep connection to Balochistan’s sporting heritage.

Cuisine

Baloch cuisine is deeply rooted in the region’s culture and serves as a core element of its identity. Among the prominent dishes, Sajji stands out as a traditional delicacy, prepared by roasting meat to perfection. Another specialty, Tabaheg, consists of salted, dried meat, often flavored with sour pomegranate and a touch of salt for preservation. In the Balochistan region, Dalag is enjoyed as one of the famous foods, commonly cooked with rice, reflecting the simplicity and richness of the food culture passed down through generations.

Festivals

Baloch Culture Day is celebrated annually on 2 March, bringing together the Balochi people to honor their rich culture and history. People from different villages gather to organize vibrant festivities, including cultural programs, folk music, and dance performances. The historical significance of this day is marked by various events, such as craft exhibitions and traditional activities, showcasing the deep-rooted traditions of the provincial state.

Religion

The Baloch people are mainly Muslim, with most following the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam, while a small number practice Shia Islam in Balochistan. Before Islam spread, they were influenced by Mazdakian and Manichean sects of Zoroastrianism, reflecting their ancient spiritual traditions.

Balochi Clothing

Balochi clothing reflects the deep cultural heritage of the Baloch people, blending tradition with identity. The attire is known for its loose and comfortable design, suitable for the region’s climate. Both men and women wear outfits that symbolize their tribal background. Women’s dresses are adorned with intricate Balochi needlework, a centuries-old art passed down through generations. These designs, made with vibrant threads and delicate patterns, represent not just beauty but also the skill of Baloch artisans.

Men typically wear long, loose-fitting tunics paired with wide trousers, which allow ease of movement in the desert landscape. A large turban or headscarf completes their look, signifying pride and honor. On special occasions, such as weddings and cultural festivals, men and women dress in more elaborate outfits, showcasing the finest Balochi needlework. The embroidery on these dresses is often detailed, taking months to complete.

In cultural gatherings, clothing plays an essential role in identity. Events like Balochi dance performances highlight traditional attire, where women wear embroidered dresses and men sport elegant turbans. Similarly, Balochi cinema often showcases traditional outfits, keeping the rich heritage alive in visual storytelling. The connection between dress and culture is deeply rooted in everyday life.

Home decor in Balochistan also reflects its culture, with the Balochi rug being a prominent example. These rugs, woven with intricate geometric patterns, are often displayed in homes and used as decorative pieces. The craftsmanship of these rugs is similar to the detailing found in Balochi needlework, symbolizing the artistic depth of the region.Despite modernization, Balochi clothing remains an essential part of identity. While some styles have evolved, the traditional essence is still preserved. Women continue to wear handcrafted dresses, and men proudly maintain their customary attire. The beauty of Balochi needlework, the elegance of cultural outfits, and the rich traditions they represent make Balochistan’s clothing heritage unique and timeless.

Clothing

The Balochi people have a rich tradition of clothing that dates back to ancient times, long before the spread of Islam. The Balochi attire, which can be seen across the borders of Balochistan in Pakistan and India, is heavily influenced by the region’s diverse history, including various dynasties. Women’s clothing is particularly unique, adorned with intricate Balochi needlework and embroidery, showcasing an art that has been practiced for over 100 or 200 years. In addition to the detailed sewing, gold ornaments such as necklaces, bracelets, and earrings form an important part of women’s clothing. The jewelry, including the popular dorr earrings and tasni brooch, is often made by local jewelers in varying shapes and sizes. These pieces are carefully designed to fasten onto the dress, especially around the chest and head, adding beauty and significance to the attire. Gold chains and heavy brooches are often worn despite the weight, symbolizing wealth and tradition, and they are fastened with great care to avoid any harm to the ears or head.

Handicraft

Balochi handicrafts are a significant part of the culture, showcasing the exceptional skill of the Baloch people. These handmade works originate from the Baloch communities in Balochistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, and are admired for their intricate designs. Balochi artisans use mirror work and embroidery to decorate various items like coats, cloth, hats, pag (traditional headwear), cushion covers, and tablecloths. The designs often include coin work and detailed embroidery, creating unique pieces like bags, shoes, and vests. These handicrafts also extend to home décor, with bedspreads, camel necks, and decorations that are displayed in rooms or hung on walls during special occasions, including weddings. The craft is popular across regions like Iran, and items can be found in local markets, reflecting the deep cultural heritage of the Balochi people.

Conclusion

The Balochi culture is rich in history and traditions that have been carefully preserved and passed down through generations. From their distinct handicrafts, such as mirror and coin embroidery, to their traditional clothing and jewelry, every aspect of Baloch life tells a story of pride and resilience. The Balochi people’s customs, like the practice of Hak Peheli, highlight their deep values of community and respect. Their unique cultural practices, including their Balochi needlework and traditional art, not only provide a glimpse into their heritage but also create a strong sense of identity. The Baloch continue to honor their past while embracing modernity, and their culture remains a powerful force in shaping the region today. As Balochistan moves forward, these traditions will continue to serve as a cornerstone of the Balochi people’s pride and unity.

Empowering businesses in Balochistan with cutting-edge digital marketing solutions! Keep innovating and making an impact!