Turbat Kech: A Unique Region of Balochistan

Turbat Kech

A Look into Turbat Kech

Turbat Kech is an important district in Balochistan, Pakistan, known for its geography, economy, and rich cultural history. Situated in the South of Pakistan, it is bordered by Panjgur, Awaran, Gwadar, and Iran. The district headquarters is in Turbat, a medium-sized urban center with a mix of Balochi, Punjabi, and Sindhi influences. The region has played a significant role in folklore, with tales such as Sassi-Punnu and Hoat, the prince, associated with its historical forts and landscapes.

Geography and Climate

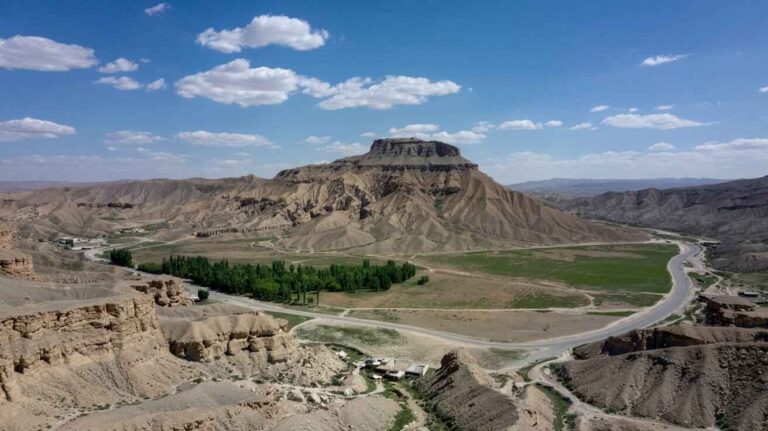

The topography of Turbat Kech is characterized by mountains, ridges, and valleys stretching in a parallel east-west direction. The Central Makran Range and Coastal Makran Range define its northeast and southwest borders, with peaks rising between 900 meters to 1400 meters. Major rivers like Kech River, Kaur-e-Awaran, Dasht Kaur, and Mand flow towards the Arabian Sea, shaping the land and livelihood of the region.

The climate of Turbat Kech is hot and arid, with temperatures soaring to 40 degrees Celsius in June. Winters are mild, with the coldest months being December to February, where temperatures drop to 18 degrees Celsius. The region receives scanty rainfall, about 109 mm annually, which is uncertain and sporadic.

Demographics and Population Trends

The population of Turbat Kech has seen a steady rise. According to the 1998 Census, the population was 413,204, increasing from 379,467 in 1981. The growth rate was 0.5 percent, significantly lower than the provincial rate of 2.5 percent and the national rate of 2.69 percent. By 2007, the urban population was 81,000, constituting 17 percent of the total population. The region remains sparsely populated, with an average of 18 persons per square kilometer, making it one of the least densely populated districts in Pakistan.

The household size in Turbat Kech averages 5.1 persons, lower than the provincial average of 6.7 and the national average of 6.9. The Baloch tribes are dominant, with Pakhtun influences in some areas. The male-female ratio remains unequal, reflecting broader South Asian trends where sons are often preferred for livelihood earning, farm chores, and economic productivity.

Economic Framework and Employment

The economy of Turbat Kech is primarily based on agriculture, trade, and remittances from workers in the Gulf States and Iran. Agriculture plays a vital role, with Machinery, irrigation systems, and land cultivation supporting livelihoods. However, employment opportunities remain limited, making the district dependent on external economic sources. The industrial sector is underdeveloped, with limited enterprises and infrastructure to support large-scale economic activities.

The 1998 Census reported a literacy rate of 27.5 percent, which is significantly lower than Quetta, Ziarat, and Punjab. The Social and Living Standard Measurement Survey (2004-05) found that literacy rates had improved to 58 percent, with 76 percent male literacy compared to 37 percent female literacy. Despite this growth, there are still gaps in education accessibility, institutional outreach, and socioeconomic inclusion.

Political Landscape and Governance

The political history of Turbat Kech has been shaped by nationalist movements, governance policies, and participatory politics. Since Pakistan’s independence, the district has witnessed political shifts, including the NAP movement, elections, and governance issues. In 2008, the district played a crucial role in provincial politics, with key political organizations influencing the elections and policy-making decisions.

Healthcare and Social Indicators

The healthcare infrastructure in Turbat Kech is relatively underdeveloped, with Basic Health Units, Rural Health Centers, and a Divisional Headquarters Hospital providing medical services. According to the National Nutrition Survey (2001-02), malnutrition, maternal mortality, and child health issues are prevalent. The Infant Mortality Rate stands at 164 per 1000 live births, while the Under-5 Mortality Rate is 130 per 1000 live births. The maternal mortality rate remains high at 880 per 100,000 births, reflecting the lack of skilled birth attendants, antenatal care, and healthcare accessibility.

Cultural and Historical Identity

Turbat Kech has a rich cultural heritage, deeply rooted in Balochi traditions, folklore, and history. The region is home to historic forts, ancient settlements, and vibrant storytelling traditions. Balochi music, dance, and poetry play an essential role in preserving the identity and narratives of the community. The district’s proximity to Iran also influences its linguistic and cultural exchanges, making it a unique hub of cross-border interaction.

Developmental Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite its economic, cultural, and geographic significance, Turbat Kech faces multiple developmental challenges. Issues related to governance, infrastructure, employment, and economic sustainability remain pressing. The district requires targeted policies that focus on community empowerment, institutional outreach, and participatory planning. Strengthening the education sector, expanding industrial enterprises, and enhancing healthcare facilities are crucial for the long-term transformation of the region.

With strategic interventions, Turbat Kech has the potential to become a key player in Balochistan’s economic and social landscape, fostering inclusive growth, entrepreneurship, and sustainable development.

Turbat and Kech are deeply connected, forming the heart of Makran, a region known for its historical significance, natural resources, and agricultural potential. The district has witnessed various political and nationalist movements that have shaped its identity over the years. From the nationalist struggle of the past to the political elections of today, the community has always played an active role in shaping its future.

The region’s farming practices, remittances from abroad, and trade ties with Pakistan and neighboring countries define its economy. The city has historically been a center for traditional farming, but with increasing mechanisation and infrastructure improvements, it holds significant potential for growth.

Agriculture and Farming in Kech

The district of Kech is well-known for its fertile lands and farming traditions. The presence of Mirani Dam has provided an irrigation reservoir that benefits areas like Nasirabad, Kalatuk, and Tump. The valleys nourished by natural streams and seasonal rains make agriculture a primary occupation. The Dasht River and Kech Kaur further enrich the land, enabling the cultivation of various food products.

The region contributes significantly to Pakistan’s national production of dates, accounting for 49 per cent of Balochistan’s yield. Kech and Panjgoor together form a major part of the national date industry, competing with Khairpur and Sukkur in Sindh. Other crops like grains, fodder, pulses, and vegetables are also cultivated, with onion, tomatoes, and chilies being the most prominent. The total cultivated area makes up 36 per cent of the district, though efforts to expand irrigation and modern technology could further increase output.

Political Landscape of Turbat Kech

The political history of Turbat and Kech is deeply intertwined with nationalist movements and elections. Since 1973, nationalist parties have played a crucial role in shaping the region’s governance. During the 1978 and 1988 elections, several nationalist leaders emerged, advocating for regional autonomy and resource allocation.

In 1997, the nationalist movement gained momentum, leading to significant differences between local and state politics. The 1990 and 2002 elections further highlighted the region’s inclination towards nationalist parties, though non-nationalist factions also participated. The alliance of nationalist parties has continued to be influential, securing seats in the national and provincial assemblies. The 2000 elections also witnessed an increase in voters’ interest, with over 12,000 votes cast in some constituencies.

The region has seen key nationalist leaders like Akbar Khan, who led various political struggles. Despite limited representation in the state government, the nationalist ideology remains strong in Turbat and Kech.

Trade and Economic Activities

The economy of Turbat Kech is fueled by trade, remittances, and agriculture. Many locals work in the Middle East, sending back foreign earnings that support the community. The city’s proximity to Gwadar Port makes it a strategic hub for cross-border trade with Iran. Markets in Turbat frequently deal in Iranian goods such as candies, refrigerators, carpets, motorcycles, and fuel. Due to limited official trade routes, many products enter the country unofficially, with transactions often occurring in Pakistani rupees, Iranian rials, or Dubai dirhams.

Historically, Makran has been a center for trade and labor migration. During the Indian Partition, many from Turbat moved to Muscat to work as laborers. Today, skilled and unskilled workers continue to seek opportunities abroad, with many earning 500 dirhams or Rs 11,000 per month.

Infrastructure and Development

While Turbat Kech has seen some modernization, much work remains. The road network connects the district to other provinces, though access to some remote areas is still limited. Electricity supply is inconsistent, with WAPDA’s power generation plant in Buleda being one of the primary sources. The Turbat airport, the fourth busiest in Pakistan, plays a key role in regional connectivity.

Despite these advancements, challenges like drainage issues in Balgattar and Dandar, and the need for better waste management persist. Private enterprises are slowly investing in the district, but more efforts are needed to harness the region’s full potential.

The Role of Livestock and Local Industries

The farming community of Turbat Kech relies on livestock for sustenance. According to the 2006 Livestock Census, around 5,000 families own milk-producing animals, including cows, goats, and sheep. The average herd size is 17 for goats, 27 for sheep, and 3,000 for cattle.

Small-scale industries, such as flour mills and mineral extraction, contribute to the local economy. Salt deposits have been reported in the region, but exploitation remains limited due to infrastructure constraints.

The Cultural and Historical Significance of Kech

The district of Kech has a rich history, dating back to Arab invaders who established cantonments in Makran. The region has retained its traditional way of life, with dates playing a central role in cultural and economic activities. Various date varieties like Begum Jungi, Haleni, Muzati, and Kaleri are cultivated in the district. The harvest season lasts from May to September, with bunches carefully thinned and ripened to ensure quality.

The practice of selective breeding has led to the development of distinct local varieties like nasabi, kuroch, and bastard. Some trees grow up to 80-100 feet with a girth of 5 feet, producing 80-120 kilograms of dates per season. Trade networks link Kech’s date orchards with markets in Sindh, Punjab, and abroad.

The cultural landscape of Turbat Kech is also shaped by its music, art, and historical sites. Efforts by the government and private organizations like the Makran Resource Center (MRC) aim to preserve the region’s heritage while promoting socio-economic development.

Turbat Kech: A Geographic and Agricultural Overview

Land and Geography

Turbat is the administrative center of Kech district, located in Balochistan, Pakistan. It lies within specific administrative boundaries marked by longitude and latitude, covering 554,336 square kilometres. The region has a diverse geographical area, consisting of arable land, barren land, pasture, and culturable waste. Its topography includes mountain ranges, valleys, streams, and rock outcrops that define the landscape. The Makran region, where Turbat is situated, has significant elevation, ranging between 100 to 1400 metres above sea level.

Climate and Environmental Factors

Turbat belongs to a temperature region with extreme climate patterns. The temperature variation is high, with scorching summers and mild winters. Due to its dry arid conditions, evaporation rates are high, making soil retention difficult. Seasonal rainfall impact affects soil formation, sometimes leading to soil degradation. However, the region benefits from natural enrichment, supporting the growth of vegetation in select areas.

Irrigation and Land Use

The Irrigation Department plays a vital role in managing irrigation water across cultivation tracts. There are multiple canals, roads, and drainage systems to aid land management and improve agriculture productivity. Despite efforts in land levelling and conservation, a large portion of reported area remains left fallow due to water logging and desert expansion. According to government statistics, only 5.2 percent of the total geographical area is used for agriculture.

Agriculture and Crops

Farming is a significant livelihood in Kech district, with key crops including wheat, barley, bakla, and masoor. Different cultivation methods are used, such as tillage, ploughing, and soil classification based on agriculture value. However, challenges like flood damage, sediment accumulation, and soil conservation issues affect overall food production. Sustainable farming practices are being introduced to enhance agriculture productivity and combat the environmental impact of climate adaptation.

Vegetation and Natural Resources

The vegetation of Turbat includes diverse plant species such as grass, fodder, barshonk, sorag, and drug. The Dasht river and its surroundings support the growth of kahur, prosopis spicigera, and gazz. Other plants like tamarix galica, tamarisk, aishak, lantoo, and danichk are commonly found in pasture lands. Shrish, chigird, kabarr, and babbur are frequently used for fuel wood and construction. The presence of nannorhops ritchieana (dwarf palm) in the mountain ridges plays a role in controlling wind erosion and protecting agricultural soil.

Energy and Fuel Resources

Turbat relies on multiple energy sources, including kerosene oil, diesel, and electricity. Many households use fuel wood for cooking and heating due to the high cost of petroleum products. The illegal trade of petrol across the Iran border affects the price difference in local markets. Liquid petroleum gas (LPG) is also used, with 58 connections reported for agricultural purposes. On average, a 40-kilogram cylinder of LPG costs around 80-85 rupees.

Environmental Concerns

Rapid urbanization in Turbat town has increased environmental threats such as noise pollution, chemical pollution, and grey pollution. The sewerage system and solid waste disposal in municipal limits remain inadequate, causing health hazards. The municipal committee uses a tractor trolley to remove household garbage from streets. However, wind erosion continues to strip the upper layer of soil, reducing its nutrients and affecting agricultural activities.

Land Use and Development Challenges

Only one-fourth of Kech district is utilized effectively. A 5.2 percent portion is used for agriculture, while the remaining land use faces issues like water shortage, soil degradation, and poor conservation practices. Employment opportunities are scarce, leading many agriculture workers to seek jobs in Gulf states. Annual rainfall of 250 mm is insufficient, making aridity a significant challenge. Protective measures like afforestation can help combat scorching heat and improve agriculture productivity.

Demography and Housing

The population of Turbat has seen steady growth since independence, recorded across four censuses (1951, 1961, 1972, 1981). The Planning Commission estimates a growth rate of 3.4 percent, with a population density increasing over time. The household structure follows a joint family system, where an average family consists of 8 members. Social norms and limited female participation in the productive sector have led to an underutilization of labor potential.

Housing Characteristics and Facilities

In 1980, the housing census showed that 94 percent of houses had one room, often used for multipurpose activities. Only 28 percent had a separate kitchen, while 38 percent had a bathroom. Latrines were available in 26 percent of homes, but very few (2 percent) had a flush system. Drinking water sources varied, with half of the population relying on open surface wells, springs, karezes, and streams.

Water and Sanitation

The Public Health Engineering Department (PHED) manages 88 water supply schemes, of which 65 are functional. Around 23.2 percent of the population receives water through pipelines and community tanks. Organizations like UNICEF and LG&RDD have worked to install 120 deep wells and hand pumps. However, the sewerage system remains a major issue, with drainage water frequently stagnating in streets.

Major Development Issues

The economic burden of Turbat Kech revolves around agriculture, irrigation, and mineral resources. Water supply remains a critical issue, affecting agricultural inputs like fertilizers, seeds, and pesticides. Due to cross-border import policies, access to petroleum products is inconsistent, affecting employment in agriculture and related sectors. Addressing health hazards through public health planners is crucial for improving awareness and sustainable development strategies.

Customs of Co-operation

In Turbat Kech, traditional Customs of Co-operation have played a crucial role in shaping the community and its socio-economic structure. The people rely on karez and karezes for irrigation, where the excavation of underground water channels requires mobilisation of local labor. These channels are maintained through reciprocal contributions from landowners and water users.

One of the significant traditional systems is sarrech, a practice where individuals share resources and responsibilities in agricultural activities. Similarly, bijar ensures that labor and materials are pooled together for major construction and farming projects. The Public Health Engineering department, in coordination with Water Management Associations, oversees water distribution, setting tariff structures to ensure sustainability.

Local committees like Anjuman Zanana Taleem, NRSP, and SPO play a vital role in community welfare and education, offering skill-based training in embroidery and tailoring. These collective efforts contribute significantly to the development of the region.

Religious Beliefs

Religious diversity in Turbat Kech includes Zikri and Sunni sects, with Nimazi followers strictly adhering to Shariah laws. The faith of the people is deeply rooted in Islamic principles, and scholars and ulema provide interpretation of religious doctrines.

Koh-i-Murad is a sacred site for Zikri followers, where special rituals are performed, especially during Ramazan. Meanwhile, Hajj remains an important pillar of Islam for the Sunni population. Religious disputes have occurred at times, often requiring arbitration to maintain harmony.

Historically, Makran has seen Islamic expeditions, and missionaries have spread religious awareness. The Buledais and Gichkis have played significant roles in shaping local religious traditions. Although sectarian differences exist, the community maintains peaceful co-existence with non-Muslims residing in the region.

Conflict Resolution

In Turbat Kech, tribal traditions play a major role in conflict resolution. Councils and committees handle disputes to prevent violence and maintain peacekeeping. Traditional mediation methods help settle rivalry and vendettas without resorting to the court system.

However, in cases of serious murder or revenge, the judicial system intervenes. Elected representatives and community leaders act as intermediaries. Zamuran and Buleda are known for their unique intervention strategies, ensuring resolution before conflicts escalate. The minister and security officials also play their part in maintaining law and order.

Arms

Illegal arms trade is a growing concern in Turbat Kech. The region’s proximity to Afghanistan and Iran has made it a hub for smuggling of weapons, including rifles and ammunition. This leads to increased crime, including robbery and murder.

Law enforcement agencies struggle with possession and trafficking of illegal arms. The district administration is taking steps to curb the availability of weapons by strengthening border controls and enhancing security measures. Crackdowns on dealers aim to reduce the turmoil caused by illicit trade.

Role, Position, and Status of Women

Women in Turbat Kech face challenges in asserting their rights in marriage, inheritance, and property ownership. Despite legal authority, economic dependence on men limits their independence. However, access to education and employment opportunities is improving.

Women contribute significantly to the embroidery sector and household income through traditional crafts. Government initiatives and advisors promote empowerment, ensuring better health check-ups and improved participation in the community. Cultural restrictions like veiling still exist, but many women continue their struggle for social and domestic recognition.

Health

The Public Health Engineering department ensures access to water and sanitation facilities in Turbat Kech, improving overall hygiene conditions. However, diseases like malaria, gastrointestinal diseases, and ARI are prevalent due to poor waste disposal.

Mother Child Health Care Centres and basic health units provide medical assistance, with Lady Medical Officers offering specialized services in gynaecology and obstetrics. However, limited medical resources and lack of trained birth attendants contribute to high maternal mortality rates.

The government is working to improve healthcare services by increasing the number of dispensaries, enhancing immunisation programs, and expanding access to emergency medical services.

Turbat Kech: A Hidden Gem in Balochistan

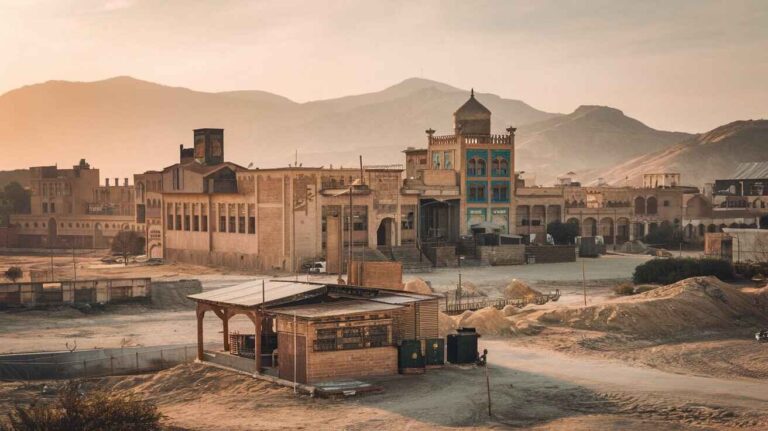

Turbat, located in Kech District, is one of Balochistan’s most historically and culturally rich cities. It has long been a center of learning, trade, and agriculture. The district is divided into several tehsils, including Mand, Tump, Balnigor, Buleda, Dasht, Hoshab, and Zamuran. The administration of Kech has evolved over time, with major subdivisions occurring in 1994 and 1995. Kech’s strategic location makes it an important hub for trade and connectivity in the region.

Demographics and Languages of Kech District

Kech has seen significant population growth over the decades. From 413,204 people in 1951, the population surged to 907,182 in 2017, and by 2023, it reached 1,060,931, marking a steady annual growth rate of 2.64%. The sex ratio stands at 109.82 males per 100 females, and the literacy rate has improved from 30.97% in 1998 to 49.65% today. However, the region still faces challenges in improving literacy rates, particularly for women and rural communities.

When it comes to languages, Balochi dominates with 99.2% of the population speaking it. Other languages like Urdu (0.2%), Punjabi (0.3%), Sindhi (0.1%), and Pushto (0.1%) are spoken by small communities. Despite the dominance of Balochi, Urdu and English are increasingly being used in educational institutions and government offices, indicating a slow but steady linguistic diversification.

Religious Composition of Kech District

Kech is home to a diverse religious community, although Muslims make up the vast majority at 99.6%. Other religious groups include Christians (0.1%), Scheduled Castes (0.2%), and others (0.1%), while Hindus and Ahmadis have a negligible presence. Religious harmony in the district is largely maintained, with different communities coexisting peacefully.

Economic and Industrial Landscape

The industry of Kech District is gradually expanding, with efforts to improve livelihood opportunities through initiatives like the South Asian Partnership. The major industrial estates include the WAPDA Power Generation Plant in Buleda, flour mills, and other small-scale industries in Turbat. Agriculture remains a key economic activity, with date farming being one of the primary sources of income for local farmers. The region is also known for its livestock, including sheep, goats, and camels, which contribute to the local economy.

Handicrafts and Cultural Heritage

Handicrafts are an essential part of Kech District’s identity. Local artisans, particularly women, engage in embroidery work and handicraft production. The Government of Balochistan has established leather embroidery centers to support artisans. Household items made from mazri palm leaves, carpet making, and other traditional crafts contribute to the region’s rich cultural landscape. The embroidery of Kech is renowned for its intricate patterns, often featuring vibrant colors and unique designs that reflect the cultural heritage of the Baloch people.

Transportation and Road Infrastructure

The roads and transportation networks in Kech serve as the backbone of the economy. The road network connects Turbat to Panjgur, Awaran in the northwest, and Pasni, Gwadar, and Karachi in the south and southeast. The domestic airport in Turbat offers direct flights to major cities, making travel more accessible for locals and businesses alike.

Road Network in Kech District

According to the Balochistan Development Statistics, the road network in Kech District consists of important roads such as Turbat-Buleda, Alandoor-Nawano, Mirabad-Rodbun, and Pasni National Highway (N-85), connecting to Hushab, Surab, Sur Chah, and various Tehsil headquarters. These roads are crucial for trade, allowing goods to move efficiently between different regions of Balochistan and beyond.

Rail and Airways

While Kech lacks a railway station, it boasts a commercial airport. The Turbat International Airport plays a crucial role in regional connectivity. The airport serves as an essential link for both domestic and international travelers, providing access to cities like Karachi, Quetta, and even international destinations. Future expansion plans aim to enhance the airport’s capacity and services.

Radio, Television, and Telecommunications

Turbat has radio broadcasting stations, including Radio Pakistan Balochistan, which serves as a primary source of information. Television access is mainly through satellite TV. The district has multiple telephone exchanges, landlines, and wireless phones, supported by broadband connections. Several cellular companies provide coverage, ensuring that residents have access to modern communication technologies. Internet access has improved significantly, allowing businesses and students to connect with the wider world.

Postal and Banking Services

The district has several post offices, with multiple courier companies operating in the region. Various banks have branches in Kech, including Allied Bank, Bank Alfalah, Bank Al Habib, Habib Bank, KASB Bank, Mybank, National Bank of Pakistan, Bank of Punjab, United Bank, and Zarai Taraqiati Bank. Both conventional banks and Islamic banks operate in the area, facilitating financial transactions for businesses and individuals.

Electricity and Gas Supply

Electricity in Kech District is supplied by the Quetta Electric Supply Company (QESCO). The transmission network supports various towns and villages. However, power outages remain a challenge, affecting businesses and households. The region is exploring alternative energy sources, including solar power, to improve electricity supply and reduce dependence on the national grid.

Educational Institutions

Education has grown in the district, with institutions such as the University of Turbat, Balochistan Engineering and Technology Campus, and Makran Medical College. Schools like Sheikha Fatima Mubarak Cadet College, Atta Shad Degree College, and multiple private schools provide quality education. Despite progress, there is still a need for better educational facilities, particularly in rural areas.

Healthcare Facilities

According to the Balochistan Development Statistics, Kech District has various government health care institutions, including teaching hospitals, rural health centers, basic health units, dispensaries, and Mother & Child Health Centers. Several private hospitals and dispensaries also operate. Healthcare access is improving, but there are still shortages of medical professionals and facilities in remote areas.

Law Enforcement and Policing

The district is divided into bifurcated towns and highways, overseen by the police force. The jurisdiction of law enforcement extends to multiple police stations under the command of the Deputy Commissioner (DC) and Assistant Commissioners. The levies force, originally recruited under British rule, operates under tribal command structures. The Regional Police Officer (RPO) Makran and Sub-Divisional Police Officer (SDPO) Turbat manage law enforcement, ensuring security across Turbat Police Stations.

Environmental Concerns

Kech District faces challenges related to air pollution, traffic congestion, and industrial emissions. Conservation efforts are needed to maintain ecological balance. Deforestation and water scarcity are growing concerns, requiring immediate attention from policymakers and local authorities.

Flora and Fauna

The flora of Kech District includes Indian mesquite, fig, date palm, Sodom apple, and lovegrass, among others. The fauna features Sindh ibex, wild sheep, Asiatic jackal, goitered gazelle, desert fox, houbara bustard, and see-see partridge. The reptile population includes Turkestan rock gecko, whip-tailed sand gecko, and Indian cobra. Wildlife protection programs are essential to safeguard these species from habitat destruction and hunting.

Protected Areas and Wildlife

The Kolwa Kap Wildlife Sanctuary is a notable district reserve, home to Sindh ibex, ravine deer, wolves, and migratory birds. Conservation efforts are crucial to preserving the region’s biodiversity. Local and international organizations are working on initiatives to promote sustainable wildlife conservation in the district.

Turbat Kech: A Land of History and Culture

The Historical Significance of Kech District

The history of Kech is deeply rooted in the ancient past, shaping the identity of Makran, a region that has witnessed great civilizations, powerful rulers, and legendary tales. Situated in Balochistan, Pakistan, Turbat has always been a significant hub due to its strategic position between the Middle East and India. Over centuries, it has been a center of trade, migration, and military expeditions.

The ancient landscape of Kech echoes with the footsteps of many historical figures. Some local traditions associate the region with Prophet Dawood, who is believed to have visited the Makran Range. Myths and folklore further enrich its history, including the tragic love story of Sassi Punnu, which finds its roots in the deserts of Makran.

The Iranian influence in the region dates back centuries, with mentions of rulers such as King Kaus, Afrasiab, and Turan. Names like Kai Khusrau, Lehrasp, Gushtasp, Bahman, Huma, and Darab frequently appear in old Balochi literature, linking Kech to the legendary Persian dynasties.

One of the most significant historical events in Turbat‘s past is the arrival of Alexander the Great in 325 BC. His army, while returning from its Indian campaign, passed through Gadrosia (modern Makran), enduring severe hardships in the barren landscape. Greek historians like Arrian documented these struggles. Later, Seleucus Nicator, a general of Alexander, took control of the region but eventually ceded it to Chandragupta Maurya in 303 BC after a peace agreement.

During the Sassanian period, rulers like Bahram-i-Gor extended their influence into Sindh and Makran, leaving behind historical traces. The arrival of Islamic rule in 643 AD changed the fate of Kech, when Abdullah Ibn Uthban, under Caliph Umer, led an expedition to the region. Historical records by Ibn Haukal, Ibn Khurdadba, Al Istakhri, and Al Idrisi mention Kech as an important trade route connecting Multan to the coastal cities. The Arab conquest also paved the way for Muhammad bin Qasim, who expanded Islamic governance in the region.

Over time, Kech became a battleground for various empires, from the Deilamis, Seljuks, Ghaznavids, and Ghorids to the feared Mongols. Local Hoths, Rinds, Maliks, and Buledais resisted foreign domination, preserving their distinct identity. The Gichkis eventually rose to power, with the Zikri faith gaining prominence through its connections with Muscat.

A turning point came in 1740, when Sheh Qasim and Malik Dinar led efforts to consolidate local rule. The region then became part of the Ahmadzais of Kalat, under Mir Nasir Khan I and later Mir Mehrab Khan. Prominent figures like Faqir Muhammad Bizanjo and local Hakims played influential roles in governing Buleda and its surroundings.

The 1838-39 Afghan War brought the British into the picture, leading to the arrival of Major Goldsmith in 1861. By 1863, the British had appointed an Assistant Political Agent in Turbat, strengthening their grip on the region. The development of a telegraph line in 1869 connected Kech to Europe through Pishin, further integrating it into the British administrative network.

In the following years, border agreements in 1872 and 1898 defined Kech‘s boundaries between Indian and Persian territories. After the Partition of 1947, Kech became part of Pakistan and later joined the Balochistan States Union along with Lasbela and Kharan in 1949.

With the creation of West Pakistan Province under the One Unit scheme in 1955, Balochistan was merged into a single administrative unit. However, this was reversed on 1st July 1970, when Balochistan regained its provincial status. The administrative restructuring of 1994-95 led to the division of Panjgur, Turbat, and Gwadar, forming the modern Kech District, with Turbat as its headquarters and the largest city in the region.