Jaffarabad: A Land Between Tradition and Transformation

Jaffarabad

Roots and Rise of a District

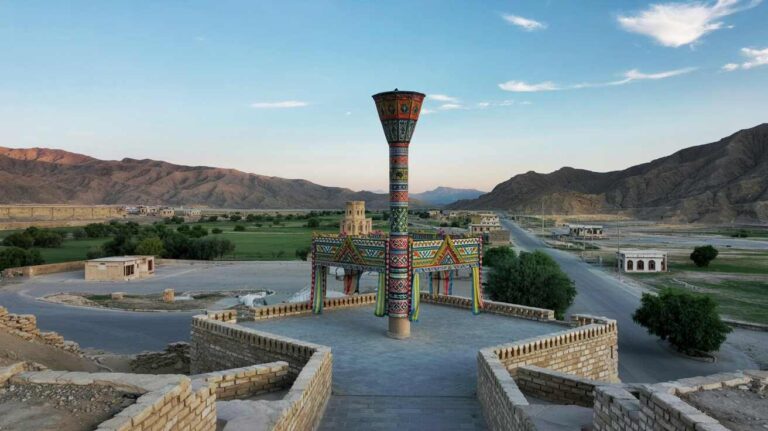

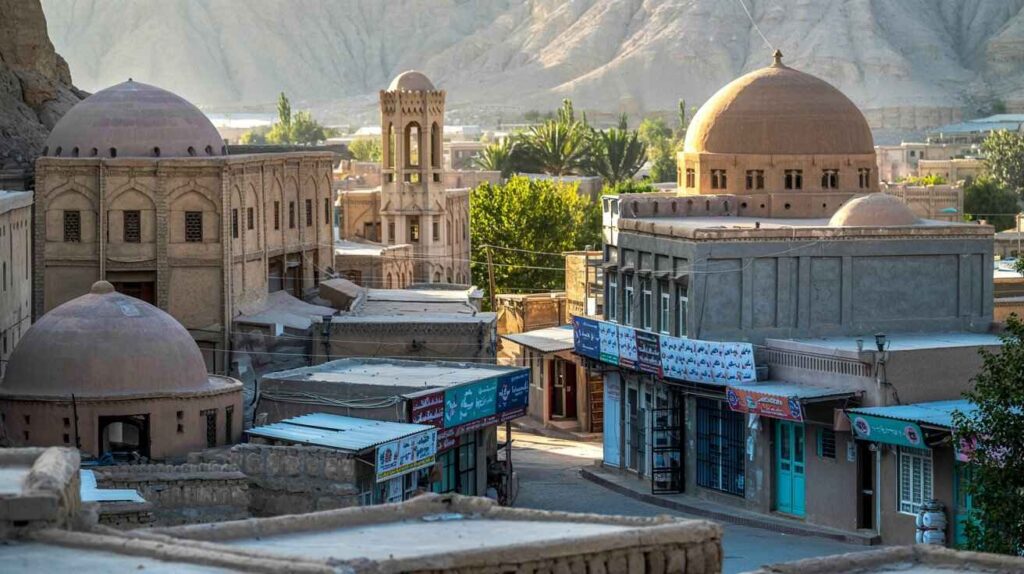

Nestled in the southeastern part of Balochistan, Jaffarabad—sometimes written as Jafarabad—stands out as a bridge between tradition and change. As someone who has visited the district numerous times, especially its headquarters, Dera Allah Yar (formerly known as Jhatpat), I’ve seen firsthand the deep-rooted tribal values and how they blend with rising urbanization and commercialization. Formed officially in 1987 and upgraded from a tehsil in 1967, this district has continued to grow in both social and infrastructural aspects. A significant shift happened in 2013, when Usta Muhammad was split off to form a new district, reshaping the chapter of this region’s governance.

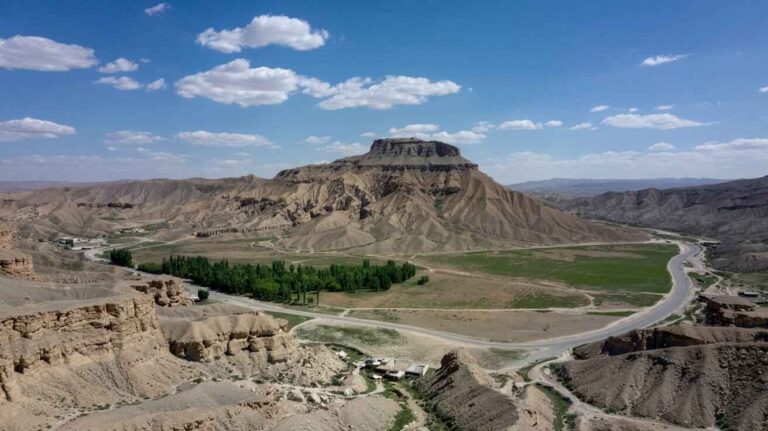

The district covers a diverse geographical area between 27° 56′ 3″ and 28° 40′ 26″ north latitudes, and 67° 37′ 36″ to 69° 07′ 39″ east longitudes, making it a strategic border region next to Sindh. It connects with Nasirabad in the north, Dera Bugti in the northeast, and Jhal Magsi in the west, while the southern edges touch Jacobabad, Larkana, and Shahdadkot of Sindh. Its main road infrastructure and link routes make it a vital hub for trade and travel between east and west of the province. The district is sub-divided into 2 Tehsils, with 20 Union Councils, and 1 Municipal Corporation, reflecting the organized layout of local administration.

According to 2023 census data, Jaffarabad holds a population of 594,558, making it the 2nd most thickly populated district in Balochistan, with a density of 0.64 million people. The local communities mainly speak Balochi and Urdu, and the area has witnessed growing awareness through mass media and improved education access. The tribe of Jamali, especially rooted in Rojhan Jamali, the native village of late Mir Jaffar Khan Jamali—a close associate of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah—continues to play a significant role in the area’s politics and society. The blend of old customs and new developments has made Jaffarabad an emblem of evolving Pakistani identity in the southeast.

Bridging the Digital Gap in Jaffarabad

During my field visit across Jaffarabad, I came across a key digital effort known as the NG-BSD Jaffarabad lot, a project that aims to improve both Voice and Broadband Internet Services across neglected regions. This lot includes Jaffarabad, Nasirabad, and Sohbatpur districts, where connectivity has long been a challenge. As someone who has worked on digital outreach projects in Balochistan, I’ve seen how this initiative focuses on the coverage of Unserved and Underserved mauzas, ensuring people in remote areas aren’t left out of the digital wave. The NG-BSD program has targeted the provision of services in areas that lacked basic voice and internet access.

In total, the NG-BSD Jaffarabad lot covers 227 mauzas, out of which 56 are completely unserved, and 171 are underserved in terms of Voice and Broadband Internet Services. The efforts are not just about infrastructure but also about unlocking educational and economic opportunities for locals. Having interacted with communities in these areas, I realized that access to digital tools can truly change lives—especially for youth and women who rely on online platforms for learning and earning. This kind of work ensures that development reaches every corner of Jaffarabad and its surrounding districts.

Shaping Identity Through History and Geography

Jaffarabad was created as a district in 1987 after the bifurcation of Nasirabad, and later further changes took place when Sohbatpur and Usta Muhammad were split in 2022 to form new districts. Originally, Jaffarabad also included Gandakha, Usta Muhammad, and other tehsils, but over the years, it has gone through administrative shifts—merged with Naseerabad in 2001, then restored as a district in 2002. This area holds both political and historical value, being named after Mir Jaffar Khan Jamali, a veteran of the Independence movement and a close friend of Quaid-e-Azam. Geographically, it lies between 67 degree 39′ West and 69 degree 12′ East longitude, and from 27 degree 55′ to 28 degree 40′ altitude, bordering the provinces of Balochistan and Sindh. This important region acts as a gateway to the Upper Sind Frontier, making it a key passage to Jacobabad in the North, Suhbatpur in the West, and Sindh in the South and East.The district of Jaffarabad consists of three Tehsils: Dera Allah Yar (also known as JhatPat), Usta Muhammad, and Gandakha, and is structured into thirty six Union Councils and around 174 villages. The 1st Tehsil, Dera Allah Yar, has 863 Streets and a Population of 226145; the 2nd, Usta Muhammad, has 507 Streets with 189372 people; and the 3rd, Gandakha, has 630 Streets and a Population of 150349. The area is known for its agricultural plains of Pat, which support a heterogeneous, composite population that includes Baloch, Sindhi, Jamali, Khosa, Gola, Jamote, and Brohi tribes. Locals speak a mix of Sindhi, Balochi, Seraiki, and Brahvi languages, reflecting the deep cultural diversity that makes Jaffarabad a vibrant and historic district of Balochistan.

DemographyAccording to the 2017 census, Jaffarabad district recorded a population of 513,813, with 51.1% males and 48.9% females. The sex ratio stood at 947 females per 1,000 males, highlighting a slight gender imbalance. The urban share was only 30.8%, and the growth rate was 3.02% across an area of 2,445 km². Jhat Pat Tehsil led with a population of 252,611 across 1,467 km², followed by Usta Muhammad with 186,226 people over 978 km², and Sohbatpur, previously part of Jaffarabad, had 200,538 people before the Gandakha region was included, holding 74,976 residents. From a linguistic perspective, Baloch was the first language for 57.31%, followed by Sindhi (14.75%), Brahi (14.30%), and Saraiki (11.62%).Education remains a tough challenge here. The overall literacy rate is 31.87%, with a sharp contrast between 43.87% males and only 19.47% females. As someone who’s worked with education outreach in Balochistan, I’ve often seen the frustration in areas where 38.60% of the population is under age 10, yet quality schooling is scarce. Despite Article 25A of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan declaring free and compulsory education for children aged 5 to 16 as a fundamental right, implementation under the Balochistan Free and Compulsory Education Act 2014 is far from complete. The BESP framework lists targets, but access, quality, and costs—from stationery and schoolbags to meals and transport—still block many from attending the neighborhood school. In terms of human resource availability, the 1998 Population Census showed 27 percent of the total population as part of the labor force, with 60 percent of the working population being self-employed, mostly in agriculture and fisheries. Unemployment rate remains high at 27 percent, with 28 percent males and just 2 percent females able to find work.

Education

According to the Pakistan District Education Rankings 2017The state of education in Jafarabad paints a mixed picture. According to the 2017 census, the literacy rate was just 36%, with a wide disparity between 43.87% for males and 19.47% for females. This gap reflects deeper issues beyond the classroom—ones I’ve personally seen while working with education NGOs in Balochistan. Despite Article 25A of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan guaranteeing free and compulsory education for children aged 5 to 16, only 4% of schools met the basic standards. Out of 113 schools, just 116 had proper infrastructure, with only 3 having electricity, 5 with working toilets, and 1 with a boundary wall. Drinking water was available in only 1 school. These shortcomings directly affect enrolment and retention rates, which stood at 89% for primary level, but dropped to 15% by class 9 and 10. Overall enrolment was 27,448, with girls’ access lagging by 28%.Initiatives like Alif Ailaan, Taleem Do! App, and the BESP framework have helped track socio-economic indicators, but political interference and poor resource management keep development slow. Despite efforts, over 97,696 children under age 10 remain out of school, and only 1 university exists to serve a region where 38.60% of the population is below that age. As per the Balochistan Free and Compulsory Education Act 2014, every child—regardless of sex, nationality, race, or disability—should have access to a neighborhood school with stationery, schoolbags, meals, and transport provided. Yet, actual delivery remains weak. With 57.31% Baloch, 14.75% Sindhi, 14.30% Brahi, and 11.62% Saraiki speakers, the lack of localized learning approaches further complicates teaching in multilingual classrooms.

Potential Sectors for Investors

Having worked closely with growers and small-scale processors in Jaffarabad, I’ve seen how the region’s hot and humid climate—lasting nearly eight months—impacts post-harvest management. This extended sun exposure and hot wind cause serious losses in fruits, vegetables, and other perishable food. Yet, these very challenges also offer untapped potential for economic progress. The region’s horticulture base can be transformed through investments in conventional and traditional techniques of preserving, freezing, and storage. Proper handling methods like dehydration, canned goods, and pickles can turn freshly harvested produce into high-demand products like tomato paste, extending freshness and increasing returns for local buyers and commerce players.With Balochistan’s rich coastal access and growing demand for seafood and fish, setting up processing factories and storages for preservation is a smart move. There’s also room for ice production to support both domestic and industrial consumption. From bakery, dairy, and hotel supplies to large-volume purchases, local professionals are ready to scale up if the infrastructure is in place. Stronger investments in this sector not only improve productivity but also stabilize prices, ensuring higher quality offerings. Jaffarabad’s position as an agro-trade gateway means there’s more than just growth—there’s lasting opportunity.