Jhal Magsi

Jhal Magsi District

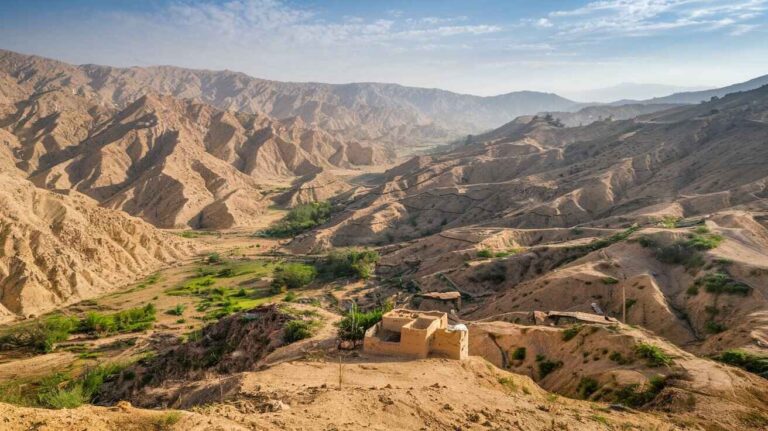

In the central part of Balochistan province, tucked between vast plains and mountainous ranges, lies Jhal Magsi, a place that carries both ancient beauty and modern charm. Officially given district status on 16 February, 1992, this area was previously part of Kachhi or Bolan District until May, 1992. The district’s name comes from the prominent Magsi tribe, known for its Baloch roots and strong presence in the region. Jhal Magsi City, along with Gandawah, forms the districts’ administrative centre. As someone who has visited many remote corners of Balochistan, the rich culture and pride of the Magsi tribe here always stood out.

The town of Jhal Magsi, known in Urdu and Balochi, played a significant role even during the colonial period. It was once a part of the native Kalat state, and today, it remains the heartbeat of the district. The Magsis, Lashari, and Lashar are major Baloch tribes here, whose ancestors migrated from Iran. Their stories echo through the valleys, especially in Kashook Valley near the Moola River, a hidden gem I personally explored during a local research trip. The present Sardar of the Magsi tribe, Zulfqar Ali Khan Magsi, a former chief minister of Balochistan, continues to uphold the tribal legacy.

But it’s not just the people and history that make this district shine—it’s the events. The famous Jhal Magsi Desert Race, held every December, brings together local and foreign drivers for an adrenaline-packed experience. It’s a tourist attraction unlike any other in Pakistan, and I’ve seen the desert car rally turn this quiet district into a buzzing celebration. The excitement draws racers from Quetta City in the north to the Sindh Province in the south, bridging communities across the landscape.

For history lovers, Jhal Magsi holds priceless treasures like the Tomb of Moti, the wife of Mir Gohram Lashari, and sacred sites such as Peer Chattal Shah Noorani, Peer Lakha, and the Sunth tail of Moola River. These ancient places serve as windows into Balochistan’s soul, hidden between the borders of Nasirabad, Jaffarabad, Khuzdar, and Bolan Districts. When I stood near Gandawah town, staring across the old tracks leading to Magsi tribal lands, I felt the deep link between land, people, and pride—something truly unique to Jhall Magsi District.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1951 | N/A | — |

| 1961 | N/A | — |

| 1972 | N/A | — |

| 1981 | N/A | — |

| 1998 | 109,941 | — |

| 2017 | 148,900 | +1.61% |

| 2023 | 203,368 | +5.33% |

People and Numbers of Jhal Magsi

Based on the 2023 census, the population of Jhal Magsi district has grown to 203,368, with around 30,953 households. The sex ratio stands at 103.49 males per 100 females, and the literacy rate remains low at 30.14%, with 37.89% males and only 22.09% females being literate. A significant portion, around 73,676, or 36.23% of the surveyed population, is under 10 years of age, which shows a young and growing community. During one of my visits for a social development project, I noticed the eagerness of children to attend school, especially in the urban areas, even though resources were limited.

Going back in time, the Census 1998 reported the District Jhall Magsi population at 110 thousand, and the projected population for 2010 was 155 thousand, showing an increase of nearly 40% or an addition of around 44,000 persons. The average annual growth rate has remained at 2.86%. Earlier Censuses, like 1951 and 1961, included Jhall Magsi as part of Kalat District, under Tehsil Bhag sub-division. Between the 1961 and 1972 censuses, the population increased by 41%, but interestingly, it decreased by -5.6% from 1972 to 1981, before increasing again by a strong 61.8% between 1981 and 1998. These shifts reflect both migration patterns and changes in local development over time.

| Religion | 2017 | 2023 | ||

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam | 147,700 | 99.19% | 201,535 | 99.10% |

| Hinduism | 1,196 | 0.80% | 1,252 | 0.62% |

| Others | 4 | 0.01% | 581 | 0.28% |

| Total Population | 148,900 | 100% | 203,368 | 100% |

Language and People of Jhal Magsi

In the 2023 census, it was recorded that 75.43% of the population in Jhal Magsi district spoke Balochi as their first language, followed by 16.33% Sindhi, 5.76% Saraiki, and 2.09% Brahui. These are the major languages spoken in the area, and despite the linguistic variety, I’ve seen that the living patterns of locals remain similar, showing strong community bonds irrespective of ethnic backgrounds. Whether it’s gatherings in town or conversations in marketplaces, the voices of Balochi, Sindhi, and Saraiki blend seamlessly into everyday life.

The majority population of the district are Muslims, mainly from major Baloch tribes like Magsi, Rind, Jamoot, and Hathyari. However, Hindus and Sikh families also live in the district as a peaceful minority, contributing to the region’s cultural fabric. What stood out to me during my visits was the shared respect among communities, regardless of their background—a quiet strength that defines Jhal Magsi’s identity.

Administrative Structure of Jhal Magsi

Jhal Magsi District is administratively divided into two tehsils—Jhal Magsi and Gandawah—along with a sub-tehsil called Mirpur. These subdivisions not only reflect the different administrative history of the region but also play a vital role in local governance and public service delivery. From my fieldwork experiences in both tehsils, I noticed how each area carries its own rhythm while still being connected through shared traditions and tribal networks.

Back in 2012, there were nine Union Councils in Jhal Magsi District, but in the last year, four more Union Councils were added. This change came following the recommendation of the Deputy Commissioner and the Delimitation Officer, and was later approved by the Local Government Department. These union councils now serve as the backbone of grassroots governance, giving local people a better voice in managing their community affairs.

District are as under:

| Tehsil | Area(km²) | Pop.(2023) | Density(ppl/km²)(2023) | Literacy rate(2023) | Union Councils |

| Gandawa Tehsil | 1,344 | 71,230 | 53.00 | 36.35% | Union Council GandawahUnion Council KhariUnion Council Patri |

| Jhal Magsi Tehsil | 1,679 | 116,528 | 69.40 | 26.82% | Union Council Jhal MagsiUnion Council HathiariUnion Council PanjukUnion Council Kot MagsiUnion Council BarijaUnion Council Mat SindhurUnion Council SafraniUnion Council SaifabadUnion Council Akbarabad |

| Mirpur Tehsil | 592 | 15,610 | 26.37 | 24.86% | Union Council Mirpur |

Education in the Land of Jhal Magsi

In Pakistan District Education Rankings 2017, Jhal Magsi district was ranked number 108 out of 141 in overall education score index, highlighting the challenges the area faces. The literacy rate for the population 10 years and older in 2014–15 was only 25%, and among females, it was even lower at 11%. During my education survey visits, the low enrolment figures stood out—just 7,553 students enrolled in class 1 to 5, and a shocking 118 students in class 9 to 10. The gender disparity issue in the district is real—only 33% of schools are girls’ schools, and access to education for girls remains a major issue.

Most schools in the district are primary level schools, making up 84%, while only 5% are high schools. There’s a serious post-primary access issue, where students simply have no schools to move on to after fifth grade. This creates a big gap, especially for girls in remote areas like Jhall Magsi, a native area of the Magsi tribe with a long colonial period history. As someone who has worked in these communities, I often saw bright, eager children left behind due to lack of opportunity and resources.

According to Alif Ailaan Pakistan District Education Rankings 2017, the district was ranked number 142 out of 155 districts in primary school infrastructure, and 141 out of 155 at the middle school level. The basic facilities in schools are lacking—more than 200 out of 301 government schools don’t have electricity, a working toilet, or a boundary wall, and 139 schools don’t even have clean drinking water. From my field assessments, I could see these were not just statistics; they were daily struggles for students.

The Taleem Do! App also reported issues like unavailability of teachers, adding to the burden. Even in important towns like Gandawah, once a provincial headquarters under Khan-e-Kalat during the colonial period, the situation isn’t much better. Despite the ancient and historical importance of Jhall Magsi, which was declared a sub-division in 1989, the current education system struggles with poor infrastructure, limited access, and unequal opportunity—especially for girls.

Archaeological Footprints of Jhal Magsi

The district of Jhal Magsi is not only known for its tribal history and culture, but also for being rich in archaeological sites and historical monuments that offer a glimpse into its layered past. From my personal journey through these forgotten corners of Balochistan, the ancient charm of locations like Khanpur, Bahltoor, and Kotra stood out, not just for their beauty but for the silent stories they carry.

Among the lesser-known yet significant sites is Dalorai Dumb, believed to be linked to a former Hindu king, a rare find in this part of the country. Nearby, Dumb Hazoor Bux quietly preserves its past, waiting for recognition. The Tomb of Moti and Ghoram, another remarkable site, reflects the local love story and tribal pride, while places like Altaz Khan Tomb, Mian Sahib Tomb, and Bhootani further showcase the region’s spiritual and architectural legacy. Each of these sites adds a valuable thread to the historical fabric of Jhal Magsi, waiting to be explored and preserved.

Climate

Climate and Weather Patterns of Jhal Magsi

The climatic conditions of Jhal Magsi district are quite similar to Sibi and Jacobabad, known for their intense heat. Summers here are extreme, with dry winds and temperatures often making daily life tough. However, the winter months bring a welcome change—the days remain hot, but the nights turn surprisingly pleasant, especially in open desert areas where locals often gather and share stories under the stars.

The rainy season usually arrives during the months of July and August, though even then, the showers are light and brief. Little rain is recorded during January, February, March, and April, but these early-year rains hold special meaning for the locals. In the local language, January and February are referred to as “lacy”, while March and April are called “chaiter”, marking a seasonal rhythm that guides everything from farming to festivals across the district.

SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

Traditional Clothing of Jhal Magsi

In Jhal Magsi, the people’s dress reflects their deep-rooted traditions and the desert climate they live in. For men, the typical attire includes a shirt, short trousers, a waist coat, and often a turban or Patkoo wrapped elegantly around the head. A pair of country-made leather shoes completes the look. During summers, their dress is usually made from thin cloth to stay cool, and they sometimes wear a Laak, a sheet of unstitched cloth used as a shawl or wrap. Some men also prefer a Topi cap, adding to the regional flair.

On the other hand, the dress of women differs from men in both style and color. Women usually wear loose trousers and a longer shirt, often made from fine silk and decorated with delicate embroidery. Their traditional look is not complete without silver jewelry, which is commonly worn during gatherings or celebrations. These styles not only show cultural pride but also tell a story of how clothing in this district has adapted beautifully over time.

Jhal Magsi District: Marriage Traditions and Family Life

In Jhal Magsi District, marriage is more than just a union between two people—it’s a matter deeply tied to tribal customs, social status, and family honor. From my personal understanding, having observed a few such marriages during cultural visits, I noticed that almost all marriages are arranged marriages, often decided by parents soon after the birth of the child. The selection of a bride is a detailed process, guided by the female family members of the groom, especially the mother, who plays an important role in all affairs related to the marriage. Factors like beauty, age, and the characteristics of the girl are carefully considered.

In the tribal setting, it’s rare to see marriages outside the tribe. Bride and bridegroom are usually matched with help from parents, guardians, and relatives, and the proposal and acceptance of the marriage revolve around the bride’s price, locally known as Taka. This amount is settled depending on the status and qualities of the girl, and it is either paid before or after marriage. This practice is common even today, and the amount can vary depending on the concerned parties. It’s a system that might seem unfamiliar to outsiders but is respected within the community.

The demand for Daj (dowry) is also a continuing practice, where the bridegroom’s family expects items like jewellery, ornaments, dresses, and household articles. In rural areas, due to poverty, some families cannot afford the bride’s price, so they rely on the Wata Sata system, an exchange marriage custom. In this, a girl from one family is married to the son of another, and vice versa. From my observation, the choice of matrimony in such systems is often imposed on the female, and majority of girls have no say in these marriages. However, in urban areas, especially among educated girls, there’s a growing tendency to consider their willingness or unwillingness in the match.

The family structure in Jhal Magsi is mostly joint, where married sons reside with parents, though nuclear families are slowly emerging due to varying levels of education and better financial positions. Family ties in the district remain strong, especially among close relatives, with elders being respected and obeyed. When the head of a family dies, near relatives take full care of the family. These bonds reflect the strong tribal life in the district, where the institution of family is seen as both a protection and a source of potential threat depending on internal differences among family members.